The Mass Line and the American Revolutionary Movement

28. The Mass Line and Proletarian Democracy

| |

THOSE WHO TAKE THE MEAT FROM THE TABLE Teach contentment. Those for whom the taxes are destined Demand sacrifice. Those who eat their fill speak to the hungry Of wonderful times to come. Those who lead the country into the abyss Call ruling too difficult For ordinary men. —Bertolt Brecht[1] |

|

Democracy—The Bourgeois Concept and the Proletarian Concept

The concept of “democracy” in modern bourgeois society is a laughable parody of the original Greek ideal. (And even that original Greek “ideal” had its own limitations, existing as it did in a society which excluded women and slaves from the political process.) But democracy in modern capitalist states has been debased to simply mean the existence of more than one legal political party—even if none of these influential parties in any way represents the desires or interests of the people—along with the existence of periodic elections to choose between them. Instead of “rule by the people themselves” democracy now only means the partial “right” to choose between candidates and programs who are carefully pre-selected and promoted by one section or another of the capitalist ruling class.

If one individual—let’s call him the “Kingmaker”—were able to select all the “serious” candidates for President, do you suppose he would much care if the final choice among these candidates was made in a mass election (which he could itself largely control through his ownership of the mass media)? He wouldn’t care a bit! In fact it would be a wonderful way to hide his actual dictatorial rule. Of course, it is not a single individual Kingmaker who rules contemporary society this way, but a class—the capitalist class.

Thus bourgeois democracy is inherently fraudulent. It is impossible for it ever to be genuine rule by and for the people themselves. Here is a summary definition of it:

| |

BOURGEOIS DEMOCRACY: The form of capitalist society in which the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie is camouflaged by superficial (i.e., fundamentally false) democratic forms. One favorite technique is to alternate rule between two different bourgeois political parties, both of which represent the fundamental interests of the capitalists and which differ only on secondary questions on which the capitalists themselves are not in agreement. The masses are accorded a minor role in deciding which of these two basically indistinguishable parties (from the proletarian point of view) shall administer capitalist power in any given period, in order to give them the illusion that they are controlling society. Whenever bourgeois rule is seriously threatened the capitalists dispense with the camouflage and resort to fascism.[2] |

|

However, while elections under bourgeois democracy are a manipulated farce, there is another aspect to it which is more important for the proletariat, and for revolutionaries in particular: the existence of some partial and limited freedoms of speech, freedoms of the press, freedoms of association and assembly, freedoms to protest, and so forth. Even in quite restricted forms these things are genuinely of importance to us, and this is why the alternative form of bourgeois rule—fascism—is far worse than bourgeois democracy. (And it is why we seriously struggle against the ever-increasing number of fascist laws as the capitalist system world-wide desperately attempts to maintain political control while it continues to sink into deeper economic and social crisis.)

However, even when we focus more on the issue of civil freedoms than on elections, we still have to say that bourgeois democracy is overall a damned poor system that the people seriously need to replace with something vastly better (true freedom and socialism). Lenin put it this way: “Bourgeois democracy, although a great historical advance in comparison with medievalism, always remains, and under capitalism is bound to remain, restricted, truncated, false and hypocritical, a paradise for the rich and a snare and deception for the exploited, for the poor.”[3]

Even the limited civil freedoms which exist under bourgeois democracy are subject to suspension or elimination whenever the capitalist ruling class sees the need to do so. As Lenin commented: “There is not a single state, however democratic, which has no loopholes or reservations in its constitution guaranteeing the bourgeoisie the possibility of dispatching troops against the workers, of proclaiming martial law, and so forth, in case of a ‘violation of public order’, and actually in case the exploited class ‘violates’ its position of slavery and tries to behave in a non-slavish manner.”[4]

The proletarian concept of democracy, while not exactly the same as the naïve concept in ancient Greece, is much more in keeping with its original spirit. It is simply the idea that the people should have real and actual control over their own lives. This control must of course be exercised in a combination of collective and individual ways, and never involve the exploitation of others. Nor can these personal and collective freedoms extend to any remaining bourgeoisie or to those attempting to re-establish an exploitative or oppressive system.

Mao summed it up well: “Democracy means allowing the masses to manage their own affairs.”[5] But some people, even some American revolutionaries, do not want to trust the masses to manage their own affairs, even with the advice and leadership of a revolutionary Party. Their attitude is not that, through social revolution, we should transform bourgeois democracy into socialist (proletarian) democracy and then into a truly complete communist democracy, but rather that no form of democracy is any good. Bob Avakian, for example, entitled one of his books: Democracy: Can’t We Do Better Than That?[6] As a matter of fact, there will still be disagreements among the people in communist society too about just how they will want to collectively manage their own affairs. And it will be appropriate and necessary to resolve those disagreements democratically.

The Contradiction Between Democracy and Scientific Guidance

In my youth, in high school, I became a really fervent believer in democracy, the classical view going back to ancient Greece that the people should themselves rule. But in college, under the influence of first Plato’s Republic, and then B.F. Skinner’s utopian novel Walden Two, I became for several years an equally fervent anti-democrat. I saw the power in such anti-democratic arguments as:

True democracy is impractical; in a huge nation (as opposed to a small village) everybody can not come together to decide even the most important issues. Instead the people have to select a small group of representatives, who theoretically are supposed to decide things in the same way that the mass of people who elected them would.

Representative democracy, however, certainly as it exists in present-day America, is almost invariably fraudulent, especially on the U.S. state and national level. The so-called “representatives of the people” seldom actually do as the people wish, and even less often do what is in the best interests of the people. Instead, most of the time—particularly on the crucial issues—they actually represent the interests of the rich. (This does not mean they are usually forced to vote against their own “consciences”; generally their consciences have been trained and transformed over long periods to reflect what is in their own personal best interests. And in this society it is in the best personal interests of politicians to faithfully reflect the viewpoint of the rich. Being a politician pays quite well once you include all the “perks” and under-the-table “favors” that come their way. Plus there is the personal aggrandizement and feeling of importance that stokes the egos of most politicians.)

In any case, government, like everything else, should be run scientifically by trained and knowledgeable specialists. I found the analogy with medicine particularly convincing. If a person gets sick, it would be foolish in the extreme for people in general, with their lack of medical knowledge, to “vote” on the medical treatment the patient gets. Instead, the best doctor available, perhaps in consultation with a few other doctors, should select the treatment. Furthermore, it is the medical community itself that is most able to determine who the best doctors are—not the people in general, who have not had the opportunity to carefully investigate the records of the many individual doctors.

If medicine should thus be run scientifically by specialists, why shouldn’t government be run the same way?

And yet, and yet, ... the gnawing feeling persists that even specialists and “experts” cannot be fully trusted, especially when it comes to the basic questions of the life and welfare of the people. (Even though we do commonly trust doctors with our very lives!) What is to keep these “governmental experts” from being bought and controlled by the rich in the same way that existing politicians are? Aren’t existing bourgeois politicians in fact “government experts” themselves?!

There is another, deeper, problem with the idea that experts should govern or guide society: the problem of who it is who will guide the experts. Sometimes when an expert is called in it is obvious what the problem is and what should be done about it; it is only a matter of applying the person’s expertise in fixing the obvious problem. But on other occasions, it is not for the expert to decide what to do—only to decide how to do what the individual or group wants done. If you have a sink overflowing because of a clogged drain, you only need to point it out to the plumber. But if you want a new sink installed, you have to tell the plumber the kind of sink that you want first. Similarly, if you go to the doctor with a broken arm it is obvious what you want and the treatment is pretty much up to the doctor. But if you have a hip problem, and the two options are to just live with it or have a hip replacement, that should be your decision, not the doctor’s. (Though you should probably carefully discuss those options with the doctor to make sure you fully understand them.)

Actually, most of the time it is appropriate for experts of any kind to do their work only after full consultation with their clients (i.e., those they work for!), and only with their clients’ full approval and authorization. There are obvious exceptions, as when a doctor must treat a person who is unconscious, but this is still the basic rule.

The Roman writer Terence remarked: “Look you, I am the most concerned in my own interests.”[7] The most concerned, no doubt; but perhaps not always the very best judge! Nevertheless, there is at least some considerable truth to the view that overall, or in general, the individual is the safest judge of his or her own personal interests. And for the same reasons, when it comes to groups of people, including social classes, it is those groups or classes themselves which should generally be viewed as the safest judge of their own common, collective interests.

Here is something to think about: The revolutionary party of the proletariat is itself sort of like an organization of “experts” (relative to the class as a whole and the broad masses), and it is the proletariat and the masses who the Party works for (not the other way around!). The Party’s expertise comes from a study of similar class struggles in the past and in other countries, and in their experience of participation in numerous previous struggles; and also from a serious study of the objective situation the proletariat currently finds itself in. But as a group of relative “experts”, shouldn’t they also consult with the masses before deciding how and where and when to lead the masses? If the general rule is that experts must consult with their “clients” about what should be done, then the revolutionary Party must do the same thing. In other words, it should be obligated to use the method of “from the masses, to the masses” (the mass line)!

But let’s talk about all this some more. One aspect of the difficulties here is well-expressed by Marx in his 3rd Thesis on Feuerbach[8], where he raises the issue of who is to educate the educators; or, in our current context, just who is to educate the experts in the first place. And who is to determine just who the real experts are? A self-perpetuating caste of rulers, as in Plato’s Republic?? In reality, social expertise comes primarily from social practice, along with the serious investigation of other social practice. And thus the “expertise” of the revolutionary party comes primarily from its participation with the masses in their current and previous struggles. As Marx implied, revolutionary expertise comes ultimately from the revolutionizing practice of the masses as a whole.

There are objective scientific standards in medicine which determine whether doctors are performing well or not—especially the health of their patients. But what are the objective standards in the case of the scientific guidance of society? Well, the satisfaction of the needs and interests of the people, of course. But how is this to be measured? Through opinion polls and “approval ratings” of the leaders? (Even though public opinion in present society is dominated by the all-pervasive bourgeois indoctrination?) Or through elections between hand-selected representatives of the capitalists??

Even in a field such as medicine there can be very serious problems with the self-perpetuation and self-guidance of the experts. The medical profession as a whole has to be guided and seriously redirected at times from the outside, by the broader society. (And in extreme cases some medical “experts” must be expelled from the profession or even be arrested and imprisoned, though this seems to be done much less often than it should be in our selfish, profit-driven capitalist world.)

A notorious example of how bad medical self-guidance can be handled even within U.S. government health agencies is the outrageous case of the immoral 40-year long study of untreated African-American men with syphilis, a very serious disease which can lead to blindness, heart damage and death. The U.S. Public Health Service along with the Communicable Disease Center in Atlanta [now renamed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] began a program in 1932, officially referred to as the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male”. This was a study of poor Black men in rural Alabama who were secretly diagnosed by public health doctors as having syphilis, but were not told about this. (They were often told such things as that they had “bad blood” about which nothing could be done.) They were left untreated, even when very effective medications became available (such as penicillin in the 1940s), because the racist doctors and officials wanted to just watch and see how the disease would develop over time.[9]

Even when a few decent people learned about this outrage and tried to stop it, it continued for several more years. “In 1965, Dr. Irwin Schatz, a cardiologist, wrote an outraged letter to the senior author of one article [related to the Tuskegee Study] calling for doctors to ‘re-evaluate their moral judgments.’ He never heard back. Bill Jenkins, a Black statistician with the Public Health Service in the 1960s, also raised alarms but received pushback from his bosses, and his efforts to interest the news media went nowhere.”[10] Finally, in 1972 Peter Buxtun, a venereal disease investigator for the Public Health Service, turned his files about the Tuskegee Study over to reporters for the Associated Press (AP). The public exposure of this long-running crime did finally lead to its termination, but it seems that neither the lead or participating culprits behind the whole thing were ever punished for these evil experiments.[11]

As bad as this example was, even much worse examples can be pointed to, including in Nazi Germany and fascist Japan in the 1930s and 1940s, and in their colonies. We won’t detail them here.[12]

The obvious conclusion from cases like this, and from the vast number of much less extreme examples—but where a great many individuals have indeed still been harmed by the indifference or incompetence of medical and other experts—is that experts too must not be given a totally free hand. They must be authorized, watched and supervised. This goes for the proletarian Party, too, especially once it achieves political power in the era of socialism. The Party must be supervised, and when appropriate, criticized and corrected by the working class and masses themselves! This is what mass struggles like the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China are all about. The more the Party uses the mass line method of leadership, the easier it is for the workers and the masses to keep control of their Party and keep it on the path of truly working 100% for the people.

So we do need experts (including the political expertise of a leading revolutionary Party) but we also truly need genuine democracy (a system where people really do collectively and individually control their own lives, and where they themselves really do get to decide what to do). What this comes down to is that “controlling your own lives” has to mean in part also being in real control of the experts you have working for you! Yes the working class and the masses really do need to hear the ideas, explanations and proposed changes by the masses that the Party suggests (many of which come directly from among the masses in the first place). But it still needs to be up to the people themselves if and when they want to try to adopt and implement those changes. The final say must be in the democratic hands of the majority of the people, and not in anybody’s orders from above!

Of the two contradictory poles, mass democracy and political expertise by the Party, the former must be principal, and the latter has to be subordinate.

This still leaves open the question of exactly how the revolutionary proletariat should go about setting up a socialist society in which they can first solidly establish and then maintain their own democratic control. We frequently talk about this general issue throughout this book. But most importantly of all, it is necessary to emphasize that a key and absolutely essential part of this is for the proletariat and its Party, working together, to institute from the very beginning of the establishment of this Party, the conscious practice of mastering and insisting on using the leadership method of “from the masses, to the masses” (the mass line). Only if this form of leadership by the Party is general and routine, and deeply enshrined in long-term practice, will there be any reasonable hope that the working class and masses will be able to maintain control of their Party during the fairly long socialist transition period to communist society.

Mass Line Democracy is the Only Practical Real Democracy in Mass Society

I take what may be viewed as a rather extreme stand on the question of the relationship between the leadership method of “from the masses, to the masses” (also known as the mass line) and proletarian democracy. I maintain that:

- The mass line, correctly understood and implemented, is a very democratic method of leadership;

- The mass line is the primary and basic method of democratic leadership; and

- Real democratic leadership that is also in the long term interests of the people requires the use of the mass line. There can be no truly good representative democracy without the mass line.

I am sure there are some who even if they grant point one, will balk at points two and three. I will try to establish all three points in this chapter and elsewhere in the book.

I will start by first attempting to consider seriously the bourgeois argument that the mass line is not democratic at all; that at best it is a kind of “elitist paternalism”.

The Bourgeois Argument that the Mass Line Leadership Method is Undemocratic

Chapter 34 will survey the general views of bourgeois writers on the mass line, and in particular their various opinions about whether or not the mass line is a form of populism or just “a communist trick on the masses”. But in this section I want to discuss one of the more sophisticated bourgeois critiques of the mass line which I have come across, a critique that claims that the mass line is inherently and essentially undemocratic. I am referring to Pat Howard’s book Breaking the Iron Rice Bowl.[13]

Some books only have any importance because they are so instructively wrong-headed, and Howard’s is one of them. Basically her book examines the experience of the Chinese peasantry since the 1949 revolution, and especially in the early post-Mao period, and comes to the conclusion that both “market socialism” and western-style (bourgeois) democracy are needed in China. I would characterize her as a social democrat, or at least as someone who is very sympathetic to the bourgeois-reformist pole within Chinese revisionism.

I cannot digress here to criticize her erroneous arguments about the possibilities of “market socialism”.[14] However, another major secondary theme of her book is that the mass line is undemocratic, and I want to consider her arguments on that issue carefully. I will start by giving her the floor with the following extensive quotations. Note well that she fails to draw any major distinction between the mass line under Mao, and what was initially still being called “the mass line” as it was applied by the revisionist usurpers (or capitalist-roaders) after 1976. To begin with, she is talking about various measures (inspection tours, surveys, conferences, etc.) that were employed by the revisionists in implementing their anti-collectivist “rural reforms” of 1983:

| |

All these measures are meant to improve the party leadership’s understanding of needs, problems, and developments in the countryside. In this way the party attempts to carry out the mass line in rural policy formation, that is, to synthesize the ideas of the peasants and give them back to them in the form of a systematized set of concepts and policies. This is essentially the same communication theory and practice applied in the land reform and the cooperation movements. It works well in a relatively small geographical area, but when translated into national policies it often leads to trouble. What is appropriate for one group of peasants at a particular moment in their shared historical experience may not be at all appropriate for another group. When the mass line is used to rationalize a universalizing impulse to transform institutions “with one slice of the knife,” people tend to lose control over their situation, to lose any sense of their function as active subjects making their own history.[15] |

|

Earlier in the book she illustrated this point in discussing the land reforms which took place in the early 1950s:

| |

The speed and administrative nature of land reform in the South caused many peasants to identify it as something imported from the outside. Underlying this problem is a tendency to treat “peasants” as a mass, so that applying the mass line can mean taking the ideas and practical experiences of peasants in one part of the country and applying them to peasants in another area despite considerable cultural and even socioeconomic differences.[16] |

|

Returning to her discussion of the use of the “mass line” by the revisionists in the 1980s, she says:

| |

The mass line is not and cannot be a substitute for national debate about alternative rural development policies. It is undemocratic for the party to draft rural policies on the people’s behalf no matter how hard it tries to keep a finger on the pulse of the nation. The current leadership may be well-intentioned, but their exercise of leadership is paternalistic and not democratic.[17] |

|

Howard sums up her critique of the mass line and democracy near the end of the book. The “authoritarian proscription” she refers to initially here is the set of general guidelines for politics, laid down originally by Mao, and known as the “four principles”—socialism, the dictatorship of the proletariat, Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, and the leadership of the Communist Party.

| |

There is no real contradiction between this authoritarian proscription and the party’s continued espousal of the mass line as a method to democratize cadres’ style of leadership. For the mass line notion of democracy rests on fundamentally undemocratic elitist assumptions....[18] The mass line is used to mobilize popular support for policies initiated by the party. Popular participation is largely limited to implementation of the party’s policies. The character and agendas of mass organizations and popular participation are skillfully engineered by party cadres and the party leaven within each organization or community. When effective, the mass line stimulates a seemingly more democratic style of work. Relations between leaders and led are more open, direct, and accessible. They are skilled at persuasion and avoid commandism. But what is replacing authoritarianism is not democracy but paternalism. The mass line does not alter the fundamentally undemocratic reality of systemic preservation of relations of domination and subordination....[19] As for the masses’ relation to the party, there is no right of recall. There is not even

a right to question the party’s mandate to plan and guide the country’s development and

socialist transition. In such a context, the party’s close attention to the opinions of the

masses becomes a matter of legitimating a basically paternalistic relationship. The mass

line is not a vehicle for popular democratic control over the party. However, in the name

of the mass line, the party can and has initiated movements for the airing of contentious

views including criticisms of the party’s exercise of leadership. But in the end, the party

usually “systematizes the ideas of the masses” by deciding which are correct and which are

incorrect. Once an idea has been defined as incorrect, it is no longer safe to pursue it.

The phase of collecting opinions is over and the masses must listen to the cadres’

explanation of the correct line that they should embrace wholeheartedly as their own. None of this would be quite so problematic if the party’s popular mandate were subject to routine validation in contested national elections. But since it is illegal to organize any political party that could openly offer an alternative program for citizens’ consideration, evolution of such a pluralist political system seems highly unlikely in the near future.[21] |

|

Howard readily admits that Mao and the Communist Party did great things for the peasants, and that the peasants recognize this full well: “Peasants generally recognize the great contributions the party made to their liberation from the tyranny of landlord rule and the constant terror of economic ruin and starvation.”[22] But she says that “in my opinion the stage of paternalistic rule on the people’s behalf has outlived its usefulness.”[23]

Well, what are we to say about all this? The things that strike me first of all are the utter lack of a class perspective and the consequent total failure to distinguish between the use of the mass line in Mao’s day, and the so-called use of the mass line by the revisionists after Mao’s death and their coup d’état. But I will come back to these points in a bit. For now, let’s play along with Ms. Howard and ignore those crucial facts. Let’s assume she is really talking about the genuine mass line as practiced by Mao, and not the bastard imitation that she came to know in her experiences and investigations under the revisionist regime of the capitalist-roaders. It would be all too easy to simply dismiss her charges based on the fact that her views were formed by investigating a counterfeit socialist society. But our goal here is not simply to shoot down all objections to the mass line, but to really think about them to see if there just might be some germ of truth here and there. So let’s consider her argument point by point in relation to the real mass line.

First the point about geography. Howard says that the mass line “works well in a relatively small geographical area” but leads to trouble when applied nationally or in regions far removed which may have “considerable cultural and even socioeconomic differences”. If all she were saying here is that the mass line can be misapplied, that it is possible to improperly generalize the experience of one locale and apply it mechanically elsewhere, then we would of course have to agree with her. Such things are possible, and do happen sometimes. But that only shows that those applying the mass line should not be mechanical, should pay very close attention to the particularity of contradiction, and to differing circumstances in different locales. Any tool, even the very best, can be misapplied or misused. This is never much of an argument against using that tool properly.

But Howard seems to be saying much more than this; that it is always impossible to generalize from one locale to other locales. There is no reason whatsoever to believe she is right about that implication. It is to argue that because mistakes are sometimes made in generalizing experience, it is never possible to do anything right on a large scale. An implication of Howard’s view is that “combining the general with the particular” is always doomed to failure, and that no single sparks can ever ignite prairie fires. This all sounds like typically unfounded and dogmatic bourgeois negativism and obstructionism to me; and she does not really attempt to present much of a case to support her cynicism. In fact she even admits that Mao and the CPC were able to lead the peasant masses to liberation from “the tyranny of landlord rule and the constant terror of economic ruin and starvation” on a nation-wide scale, though she fails to explicitly acknowledge that their use of the mass line had anything to do with this. (And it had a lot to do with it!) But evidence such as this does clearly show that local experience can be generalized successfully, and that the mass line can be successfully employed on a nationwide scale.

Ms. Howard fails to mention Mao’s frequent admonitions to local cadres to only proceed with general policies (such as collectivization steps) when local conditions are right. She does not mention that the pace of change was frequently much slower in minority nationality areas, for example. Mao and the Party center could have ordered that otherwise nationwide changes be extended to these special areas as well, but they didn’t because they appreciated the fact that local conditions were not yet ripe, and that the masses there had to make the changes themselves when they were ready.

An important point about the mass line which Howard completely fails to understand is that when properly applied it is reiterative and self-correcting. Of course we try to avoid mistakes, but we do not unduly fear them. If we make mistakes in our political work, it will become obvious, and we will correct them. If the mistakes are so serious that our overall goal cannot be achieved, we will simply start again. If something works in one area, but not another, then we will reapply the mass line in the regions where the old policy failed, until we come up with a line and policy that is successful in the new regions. Any invalid generalization of experience should thus have a quite limited potential for doing permanent damage as long as we really remain true to the mass line method of leadership.

Of course some mistakes were made in the collectivization of agriculture in China. Any massive change like that is bound to have lots of rough edges. To some extent the experience of certain test regions was applied prematurely, or tardily(!), or otherwise improperly in some other areas (by no means all!). That is one of the kinds of mistakes which are inevitable to some degree in any great social transformation. But the point which Howard completely “forgets” is that overall the collectivization of Chinese agriculture was successful and was done quite well. Overall, the experience of test localities was correctly applied on a nationwide scale. It was done far more smoothly, and far more correctly, than the corresponding change in the Soviet Union, for example. There will always be mistakes and shortcomings in our leadership work, but if these are strictly secondary, and easily corrected, we and the masses are progressing just fine. To refuse to advance because some mistakes might be made, or even because we know that in the best of cases there will still be some secondary mistakes, is to refuse to advance at all. It is to favor the status quo, or in other words the bourgeois system.

Ms. Howard combines her geographic argument with the implication that the mass line requires that massive changes be carried out in one fell swoop, all at once and everywhere, rather than step by step, and as appropriate region by region: “When the mass line is used to rationalize a universalizing impulse to transform institutions ‘with one slice of the knife,’ people tend to lose control over their situation, to lose any sense of their function as active subjects making their own history.” However, there is nothing about the mass line method which requires that social change be carried out “with one slice of the knife”, everywhere and all at once, when such a course is not appropriate.

But what Howard cannot appreciate is that often the force of circumstances, and the masses themselves, demand that long-overdue changes be brought about immediately when they hear that they are being brought about elsewhere. In other words, a single spark really can ignite a prairie fire. In such a situation the party is often forced to scramble to keep up with the masses. When the mass line is used correctly, this situation will almost be typical. And to say under such circumstances that the people “tend to lose control over their situation” is the exact opposite of the truth. It is the authorities who tend to lose control to the masses under these circumstances, and a damned fine thing it is too! Whether it is the bourgeois authorities under capitalism, or a new bureaucracy under nominally proletarian rule (perhaps becoming a bit stodgy, and already becoming a bit conservative) that loses control—either way it is a damned fine thing. It is a liberating thing for the masses.

Just because there is a bit of chaos and confusion, it does not follow that the masses have lost control of their own destiny. On the contrary, a sign of the masses taking control of their own destiny is inevitably a bit of confusion and disorder at first. Social progress is not made in an entirely “orderly” fashion; a breakdown of the old “order” is an essential part of the establishment of new order. Essentially bourgeois types, like Ms. Howard, are always horrified by disorder, and imagine that it means the world is going to hell, that society is “out of control”. In fact, spirals of order, disorder, and order again are the only road “to heaven”, to a fundamental change in society for the better.

Howard continues her critique by arguing that the mass line is undemocratic—the argument which we want to examine with special care in this chapter. She starts with the general comment that “It is undemocratic for the party to draft rural policies on the people’s behalf no matter how hard it tries to keep a finger on the pulse of the nation.” This goes against the fundamental reality of political parties representing the interests of social classes. If the party of the proletariat and the masses cannot democratically represent the proletariat and the masses, and lead them, then who can?? Howard seems to desire an abstract “democracy” without leaders. She seems to be against any representative democracy where a party represents a class, or alliance of classes, and in favor only of the crassest form of bourgeois populism—where the leaders do not really lead at all, but only tail after the masses. According to this logic, any kind of leadership is “undemocratic”, because it means trying to bring the masses to support plans and policies which the majority originally did not support.

Bourgeois conceptions of democracy are incredible! The basic bourgeois conception is that democracy consists entirely of the right to chose between more than one party in formal elections. Thus if the bourgeoisie has two essentially identical parties which monopolize politics (through their wealth, and control of the media and society as a whole), and the only choice the masses have is to occasionally chose which one of them will administer their own oppression—that is “democracy”. The bourgeois populist addition to this is that it is “undemocratic” to try to lead the masses along any path which they do not favor from the very beginning—even if such a path is really in the masses’ best interests. But there is no reason in the world why the concept of democracy should be delimited with such simple-minded bourgeois absurdities as these.

Of course we Marxists have a completely different conception of democracy than the bourgeoisie! We do not apologize for the fact; we are proud of it! Our conception of democracy is a society ruled by the masses on a day-to-day basis, where the multitude of decisions made everyday which affect the masses are made by the masses and in the masses’ interests. We are trying to help lead the masses in the construction of such a society. Compared to this the occasional right to chose between essentially identical parties in some formal election, both of which represent an alien exploiting class, is a negligible and ridiculous trifle.

I am not saying that more than one proletarian party cannot, or should not be allowed to exist under proletarian democracy. In fact, I think that while such an arrangement would inevitably foster more disunity among the proletariat than is desirable, it would still be wrong to try to suppress additional working class parties that were not opposed to the socialist system. Neither am I saying that the choice between two such parties in elections would necessarily be inconsequential. At times it might become critically important. But the main point is that the principal content of proletarian democracy is the real control by the masses over their daily lives, not the question of whether there is one proletarian party, or several proletarian parties to chose from in elections.[24]

Ms. Howard continues with her critique of the mass line as undemocratic with the statement that the mass line “cannot be viewed as an instrument of democratic self-government or popular control over policy formation...”. She is willing to admit that a virtue of the mass line is that it allows the masses considerable say in how policies are implemented, but does not see that the masses have any part to play in the original formulation of the general policy which they themselves then implement. This is just to say that she does not really understand the mass line; or, the only “mass line” she understands is the bastardized version occasionally practiced by the revisionist usurpers in China after Mao’s death.

Evidently the phrase “From the masses, to the masses” means nothing to her. Or perhaps she views it as a big lie, or as self-deception on the part of the Maoists. She does not examine at all Mao’s explanation of how the correct line or policy is derived from the ideas of the masses. She simply ignores all that, and asserts without any evidence or argument that the masses do not have any control over policy formation.

It is true, of course, that the decision as to which of the ideas of the masses is to be selected as the basis for a political line or policy is made by the leadership of a party which has itself grown out of the masses. But the stock of possibilities comes first of all from the masses themselves. True, it may not be a line already championed by the majority, but it is a line which some at least among the masses already champion, and which the party learns from some of the masses.

Furthermore, the third step of the process is taking this line back to the masses; that is, taking it back to the great majority of the masses concerned. Here too is part of the democracy of the mass line. If the masses in general do not accept the processed line from the party leadership, and refuse to implement it despite all the urging from the party, then the only thing to do is to go back and develop another line that they will generally accept, from the stock of ideas gathered from the masses. The masses should always have the final say in the matter.

“The mass line is not a vehicle for popular democratic control over the party,” says Ms. Howard. Of course, Mao said just the opposite; here are just a few of the dozens of quotations I could site:

| |

Let me repeat. Correctly handling the contradictions among the people means following the mass line, which is consistently stressed by our Party. Party members should be good at consulting the masses in their work and in no circumstances should they alienate themselves from the masses. The relation between the Party and the masses is like that between fish and water. Without good relations between the Party and the masses, the socialist system cannot be established or once established, be consolidated.[25] By now you should know well the characteristics of the government. We are the same group. We consult the people, the workers, the peasants, the capitalists, the petty bourgeoisie, and the democratic parties on whatever we plan to do. You can call us the consulting government. We do not put on a stern face and lecture people. We do not give anyone a stunning blow if his opinions are not sound. We are called the people’s government. You may bring up whatever ideas you have. We don’t ill-treat people under any pretext.[26] Our Party has a democratic tradition. Without this tradition it would have been impossible to accept such free airing of views, great debates and big-character posters.... In the days of the agrarian reform, we consulted the masses whenever problems arose in order to straighten out ideas.... But the free airing of views and the holding of great debates, to be followed by consultation and persuasion in the nature of “a gentle breeze and a mild rain”—it is only now that all this can come about. We have found this form which will immensely benefit our cause and make it easier for us to overcome subjectivism, bureaucracy and commandism (by commandism we mean striking or cursing people or forcing them to carry out orders) and for leading cadres to become one with the masses.[27] Politics must follow the mass line. It will not do to rely on leaders

alone. How can the leaders do so much? The leaders can cope with only a

fraction of everything, good and bad. Consequently, everybody must be

mobilized to share the responsibility, to speak up, to encourage other

people, and to criticize other people. Everyone has a pair of eyes and a

mouth and he must be allowed to see and speak up. Democracy means allowing

the masses to manage their own affairs. Here are two ways: one is to depend

on a few individuals and the other is to mobilize the masses to manage

affairs. Our politics is mass politics.... In advocating freedom with leadership and democracy under centralized guidance, we in no way mean that coercive measures should be taken to settle ideological questions or questions involving the distinction between right and wrong among the people. All attempts to use administrative orders or coercive measures to settle ideological questions or questions of right and wrong are not only ineffective but harmful. We cannot abolish religion by administrative order or force people not to believe in it. We cannot compel people to give up idealism, any more than we can force them to embrace Marxism. The only way to settle questions of an ideological nature or controversial issues among the people is by the democratic method, the method of discussion, criticism, persuasion and education, and not by the method of coercion or repression.[29] |

|

Clearly, for Mao and all true Maoists, there is a close connection between the mass line and democracy. Both the masses, on the one hand, and the Party and the government, on the other hand, should influence and “control” (lead) each other through democratic, mass line means.

There are two reasons why Ms. Howard cannot understand and agree with Mao. First, her experience with the “mass line” is under the early rule of the capitalist-roaders, the revisionists in the Party leadership who wanted to develop China via capitalism. This meant that their conception of the “mass line” was totally distorted and perverted into its political opposite. But even more basic than that, it is because her conception of “popular democratic control” differs from the Maoist conception. For her it is not a case of people controlling their own lives, and of learning how to do so to an ever greater degree. For her no learning, no leadership, is allowed. For her it is entirely a matter of opinion polls and formal elections based on static initial ideas.

In the sense that bourgeois populists understand the phrase “popular democratic control”, it is only the immediate, total, and uncritical absolute reflection of the initial ideas of the majority. So, from this populist point of view, the mass line is supposedly “not democratic” since it disagrees with this static and tailist approach. The mass line, as Maoists understand it, is a method of first attempting to change the ideas of the majority of the masses by starting with the advanced ideas of a minority, and popularizing those more advanced ideas as broadly as we can. We then seek to lead the masses on the basis of those now more widely appreciated advanced ideas about what to do to advance their own interests. It is still ultimately up to the masses themselves whether they want to implement these changes. So the mass line is definitely a democratic method of leadership. But what Ms. Howard, and similar populists just cannot understand is that the mass line method also involves mass education, the changing of the dominant mass views before mass action and changes in society are attempted.

The mass line, the leadership method of “from the masses, to the masses”, involves education of the masses, as well as leadership. That education comes primarily from the masses themselves, from their own ranks, but then is summed up and popularized much more broadly by the proletarian Party. It is indeed curious that bourgeois populists find this whole procedure so hard to understand!

In the concluding sentence of her book Pat Howard remarks that “People must have the right to give their ideas potency by articulating them collectively so as to realize Einstein’s requirement for an ‘organized democratic counterweight to administrative power.’”[30] She completely fails to see that this is precisely one of the key things that the mass line is designed to do. Mao, for example, remarked that “We must let the people fully express themselves. Cadres must be supervised both from above and from below. The most important supervision is that which comes from the masses.”[31]

Paternalism vs. Democracy

But the accusation by Pat Howard that really alarms me, that really, truly offends me!, is that the mass line is paternalistic. I say this because I hate paternalism with a passion, and think it is perhaps the worst of all possible sins to which the “left” is prone.

Paternalism, in the Marxist view, is the method of political leadership (or a political system based on this method of leadership) wherein the authorities or leaders run things on behalf of the ordinary people, make decisions for them, and so forth, in the same way that a father might do for his young children. Even if these decisions really are for the benefit of the people for a time, this is still a perversion of Marxism, which since its founding by Marx and Engels, has always championed (at least in theory) a truly democratic society where the people make their own decisions and control their own lives.[32]

The democratic, Marxist alternative to paternalism is the leadership method of “from the masses, to the masses”, also known as the mass line method of leadership, wherein there are still leaders, but the leaders lead not by themselves deciding most things for the masses, but rather by seeking to educate the masses in their own real interests and by helping them to organize themselves to implement and satisfy those interests when they are ready to do so.

By far the worst crime of Joseph Stalin (and he was guilty of some other very serious political crimes as well!) was to rule the Soviet Union in a paternalistic manner. The masses were thus not trained to run things themselves, nor to question or resist their leaders when they seemed to be making changes that went against their own interests. Thus when Khrushchev and a new generation of leaders came to power after Stalin’s death—leaders who were now revisionists out to promote their own welfare and not that of the people—the masses were unprepared to stop them and were lost.

If the masses accept their status as children, who are being taken care of by others—even a supposed Marxist revolutionary party trying to serve their interests in the way a father might—then eventually they will be re-enslaved by a new bourgeois ruling class developing out of that once paternalistic party. That is the foremost lesson of the triumph of state-capitalist revisionism in the Soviet Union.

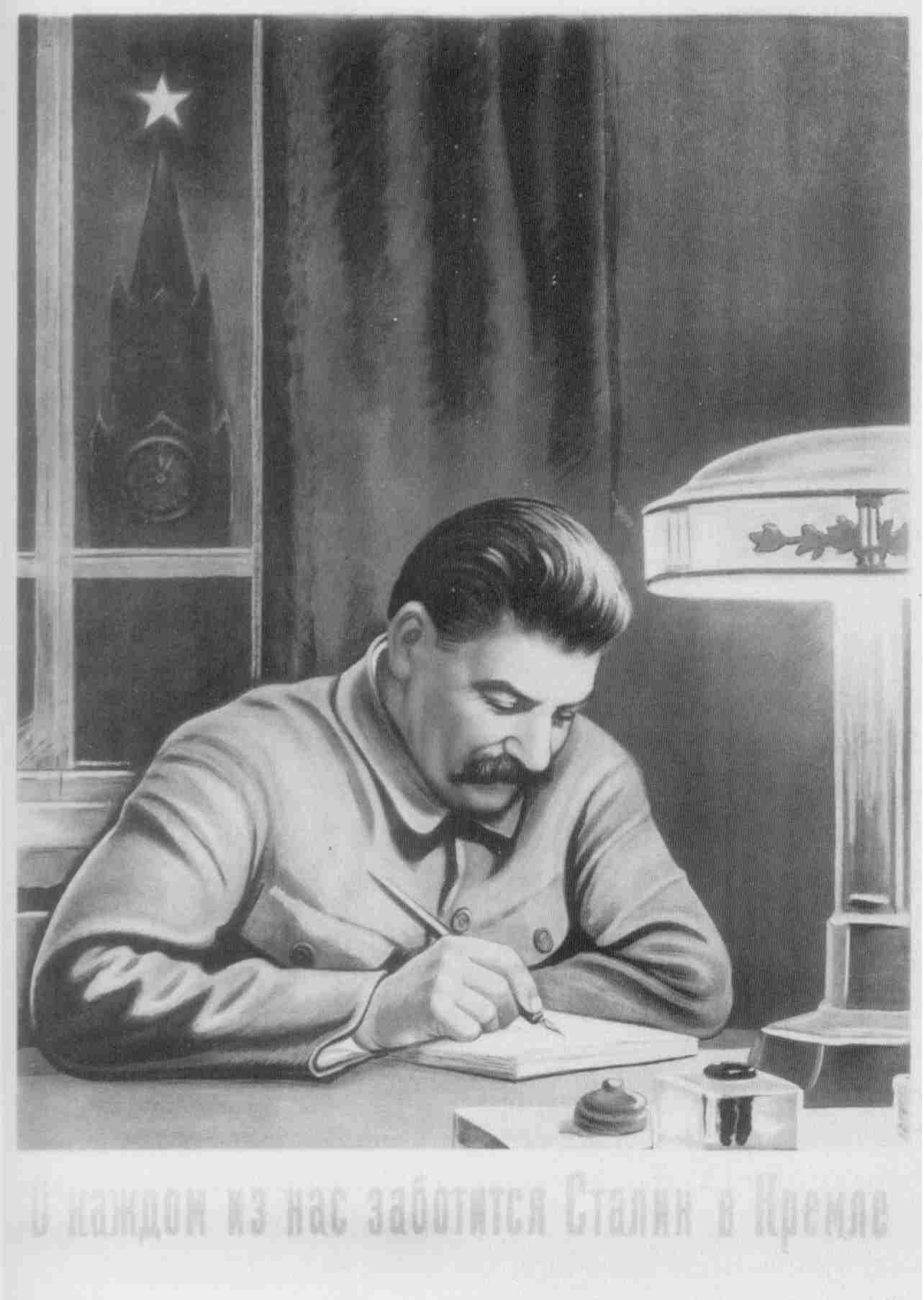

The caption on this 1940 poster says:

“Stalin in the Kremlin Cares about Each One of Us”[33]

In 1958, at the Second Session of the Eighth Party Congress of the CCP, Mao commented: “Stalin did not promote the mass line. He played favoritism and was too excessive in the class struggle.”[34] We will talk about that passage some more in Chapter 36. But in saying that Stalin “played favoritism” I think Mao was saying, at least in part, that Stalin did favors for the masses, and is thus criticizing Stalin’s tendency toward paternalism.

Paternalism is a characteristic feature of the political approach of bourgeois liberalism. Their typical pattern in American society, for example, is to seek to enact some new laws which may help or benefit the poor to some limited degree, or might conceivably help lead to some small improvements in political equality, and so forth. In certain cases we revolutionaries can also support these new laws and small improvements. But note well that this is not the main thing we are about! Our approach as Marxists-Leninist-Maoists is not to make a few superficial changes in the legal structure of society which may possibly help the poor and oppressed to some small degree, but rather to help educate and organize the people to take action themselves to advance their own interests! (And especially to start taking action in a revolutionary direction!)

It rarely occurs to bourgeois liberals to join up with the masses in demonstrations and mass actions in support of their struggles and goals. Instead, liberals like it much better when the masses are calm and passive, and the liberals themselves can step forward to “help them”, through their electoral votes and the legal program they might support. It is so much more relaxed and genteel!

Well, we rightly despise the whole approach of the liberals (even if at times we do have make short-term alliances with some of them). But we should be alert to how liberals operate, and avoid any tendencies to follow their bourgeois practices. Don’t imagine that similar approaches can never arise within the revolutionary movement!

Sometimes even some of our own Maoist slogans or basic points of view have to be examined to see if there might be false interpretations or tendencies towards paternalism involved in them. Consider, for example, our fine long-term slogan “Serve the People!” Might that be suggesting that our program is basically one of “doing favors for the people?!” Is it, indeed, a paternalistic slogan?! Well, it shouldn’t be! After all, the main ways that we work to serve the people are not at all in the way that liberals suppose they do. Our fundamental way of serving the people is by bringing revolutionary ideas to them and by participating with them in their struggles for their own interests! Still, the next time you hear a comrade mention the slogan “Serve the People”, it might be worthwhile to have just a short discussion with them about how they actually understand what serving the people is all about.

In closing this discussion about paternalism, I’d like to mention and briefly consider a very interesting comment by the great American revolutionary labor leader, Eugene V. Debs, speaking to workers in Detroit in 1906:

| |

I am not a Labor Leader; I do not want you to follow me or anyone else; if you are looking for a

Moses to lead you out of this capitalist wilderness, you will stay right where you are. I would not

lead you into the promised land if I could, because if I led you in, some one else would lead you out.

You must use your heads as well as your hands, and get yourself out of your present condition.[35] |

|

That’s a remarkable statement! Of course Debs understood that any political movement does require leaders and he himself was an important leader of the labor and socialist movements of that era, and even ran for President of the United States a number of times—once while he was in prison for opposing the U.S imperialist role in World War I. So what then was Debs trying to get the working class to understand with this remark? I think it is just the old idea that goes back to Marx: The emancipation of the working class must be accomplished by the workers themselves. If the working class instead looks for saviors to handle its liberation for it, it is bound to be disappointed and defeated in the end.

The Right-Wing Hoover Institution Also Opposes the Mass Line as “Elitist”

Pat Howard is not of course the only bourgeois ideologist to champion such themes about how the mass line is supposedly elitist and anti-democratic. Somewhat along the same lines, though perhaps a bit more to the right, are many of the comments of Peter R. Moody in his Hoover Institution book Opposition and Dissent in Contemporary China.[36] He says for example that

| |

The mass line, like what [Mark] Selden calls the bureaucratic method (allegedly favored in the Soviet Union), is a technique of control, and its superiority over the bureaucratic method is in its effectiveness, not its democracy per se.... Mass-line democracy, unlike liberal democracy, is often held to be nonelitist, although one might think that any group which refers to fellow human beings as masses shows itself by that fact to consider itself an elite.[37] |

|

Of course from the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist point of view, the mass line is in fact a method of “control”, that is, of control and direction of the revolutionary mass struggle. But what the bourgeoisie cannot understand and will in any case never admit is that it is just as much a method of control of the party by the masses as it is the masses by the party. “From the masses, to the masses.” The masses first teach or guide the party, and then the party—the most conscious and organized section of the masses as a whole, teaches and guides the rest of the masses. The bourgeois conception is that the masses and the party must be opposed, that they cannot possibly have interests in common, which they strive to achieve together. The enemy will inevitably insist that such a class perspective is invalid, which is really to argue that, despite all common sense to the contrary, the real interests of the masses lie in submission to and control by the alien bourgeois class.

Moody grants that the mass line is superior “in its effectiveness” to bureaucratic methods, though it would be embarrassing for him to really explore the question of why this might be so. (If it is just as “elitist” as bureaucratic methods, how is it that the masses are so easily tricked by such transparent methods?)

And then we come to the laughable claim that anybody who even uses the word ‘masses’ must inevitably be thinking in elitist terms! This is a corollary of the standard central dogma of bourgeois-democratic political science. All leaders, you see, are “elites”, dominating all the people they lead.” Bourgeois thinkers even think of their own liberal democratic systems this way, and of course they are quite right to do so in that case. Not all leaders, however, are elites, standing above the masses. The masses themselves can bring forth their own leaders, and the best of these people remain immersed in the masses and continue to reflect and champion the interests of the masses rather than their own separate interests.[38]

As for the word ‘masses’ itself, we Maoists use that word in a wholly different way than does the bourgeoisie and its professional apologists. To us it is not a term of derision, or of condescension. We esteem the masses and modestly try to learn from them. We view ourselves as coming from the masses and serving the masses. Of course we recognize a difference between the most organized and conscious section of the masses—the proletarian party—and the rest of the masses. But we do not view this in any way as “elitism”. More than that, we have committed ourselves to fight to the death any such elitist tendencies.

Mr. Moody, unlike Ms. Howard, recognizes that there have been two versions of the mass line in China, “the Maoist, or radical position”, and the “moderate” version (of Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping). But he thinks the differences between the two should not be “exaggerated”. He says that “The moderate view seems to entail a typical Leninist distrust of mass spontaneity,”[39] thus correctly putting his finger on one of the things wrong with the Liu/Deng version of the mass line. But at the same time he helps to perpetuate the usual bourgeois slander on Lenin. (As we saw in chapter 9, spontaneity must be viewed dialectically, as Lenin in fact did.)

Moody seems to criticize what he evidently views as the muddle-headed thinking of some western observers about the mass line:

| |

There is the impression, however, that in the Maoist version of the mass line there is more than totalitarian mobilization as a means of maintaining control under conditions of great and directed social change. Some believe the Maoist line does not fear spontaneity and implies a genuine trust in the masses.[40] |

|

But “Both versions of the mass line,” he says, “as applied to peasants, are elitist.”[41]

It’s the same old bourgeois tune: The Maoists want to lead the masses in changing society. To lead them is to get them to do things many of them did not originally want to do. Thus there cannot be any real trust in the masses, or acceptance of mass “spontaneity”. I would hope that by now you can see the absurdity of such an undialectical and generally pathetic argument.

A Chinese Sinologist Opposes The Mass Line to Democracy

A third bourgeois Sinologist commenting on the mass line is Tang Tsou of the University of Chicago. He remarks that:

| |

The mass line is not the same as democracy. [At this point he footnotes his book The Cultural Revolution

and Post-Mao Reforms: A Historical Perspective (University of Chicago Press, 1986), pp. 270-1.] Moreover,

the idea of the mass line during the period of struggle with opposing political forces [I assume he means the

Mao era—JSH] was frequently combined with the idea of “developing the progressive forces, winning over the middle

forces, and combating or isolating the die-hard forces.” It is still nothing more than a method of leadership in

a revolutionary struggle. |

|

Well in now-capitalist China the mass line (in-so-far as it even still exists at all, even in totally distorted form) is certainly no longer “a method of leadership in a revolutionary struggle,” though perhaps its occasional use may now be considered a method of leadership in a counterrevolutionary struggle!

But Tsou seems to be arguing that the mass line can’t be democratic since the whole point of it is to lead one group of people in defeating another group of people. This, of course, is the familiar bourgeois nonsense that in “truly democratic” countries like the U.S. the leaders must represent all the people. They claim to, certainly, but anybody with even the most rudimentary political knowledge knows quite well that in reality they represent only the ruling class. Liberal political “scientists” like Tsou not only proclaim the bourgeois party line, but probably even believe it.

Tsou goes on to say that the revisionist rulers of China must not simply revive Mao’s ideas such as the mass line, but must instead “fundamentally transform them from conceptions to guide revolutionary political struggle into individual elements in a fundamentally different process of contestation, negotiation, bargaining, and compromise”[43] appropriate to a post-class-struggle, depolarized, bourgeois democracy.

It is very interesting that so many bourgeois commentators on “democracy” seem to be opposed to its central aspect of a majority winning out politically over the minority. What do they even imagine democracy is for, if it is not a method of deciding what to do when there are differences of opinion?!

Why the Method of “From the Masses, to the Masses” Really is Democratic

In summary: The leadership method of “from the masses, to the masses” (the mass line) is democratic because:

The raw material for the mass line comes primarily from the masses themselves. This means both from their expressed ideas, and also from the implicit ideas in their actions.

The masses themselves decide whether to accept and actually implement the processed line or policy from the party. If the great majority of the masses really do not support the action or change, it simply cannot be successfully implemented and something else will have to be tried.

- Most fundamentally of all, the revolutionary party itself arises from and is a part of the proletariat and the masses in the broad sense of these terms. The party comes into existence for no other reason than to represent and champion the interests of the masses, and to help them achieve their own goals.

Of course this means that if the party ceases to be the party of the proletariat and the masses, if it is taken over by the class enemy in the form of a new bourgeoisie, then anything it calls the “mass line” will no longer be democratic. This is what happened in China under Deng Xiaoping and his successors. But the fact that something can be destroyed in no way proves it is not something good and useful while it still exists. The mass line is a wonderful democratic tool in the hands of a genuine proletarian party which recognizes its value and seeks to make use of it.

| |

Our idea is that a state is strong when the people are politically conscious. It is strong when the people know everything, can form an opinion of everything and do everything consciously. —Lenin[44] |

|

| |

Many people seem to think that the use of the democratic method to resolve contradictions among the people is something new. Actually it is not. Marxists have always held that the cause of the proletariat must depend on the masses of the people and that Communists must use the democratic method of persuasion and education when working among the laboring people and must on no account resort to commandism or coercion. The Chinese Communist Party faithfully adheres to this Marxist-Leninist principle. —Mao[45] |

|

Is the Mass Line Democratic in Actual Practice?

Was the mass line as actually practiced in Mao’s China truly democratic? Not always, by any means. I would be the first to admit that the practice did not always conform to the theory. It must be remembered that most of the cadres attempting to apply the mass line in China were poor or middle peasants, usually with little education, and quite often with a rather shallow understanding of Marxist theory. They joined the revolution, but they brought with them a lot of Confucian and bourgeois ideological baggage. Some of them grasped the mass line and sincerely tried to apply it, and others of them did not. If I had to guess what was most typical of Chinese CPC cadres, even during the Mao period, I would have to say those who only partially grasped the idea and method. But the mass line was strongly encouraged by Mao, and widely attempted—more so than ever before in history. Even if were true that its full and genuine use throughout China was more the common exception than the rule, it still produced wonders, and in doing so made use of and promoted democracy more than anything else ever has. Imagine how much better still the results might have been if the mass line could have almost always been correctly used!

In 1962 Mao and the CPC launched the “Socialist Education Movement” one of whose goals was precisely to correct the authoritarian work-styles of many cadres.[46] The following account of what it found in one small village in rural Guangdong Province, was written by a former Catholic missionary and is based on interviews he did with refugees of mostly bad class backgrounds who fled to Hong Kong. So despite the author’s sympathies towards the Chinese revolution, there is reason to be somewhat cautious of what he reports. Nevertheless, it is worth considering:

| |

With regard to political attitude, the work team said that the cadres should be “democratic.”

This did not mean, of course, that cadres should simply do what the majority wanted but rather

that they should follow “mass-line” principles of leadership. They should be intimately in touch

with the hopes and aspirations of the masses and formulate policies reflecting their true

interests while at the same time fulfilling the spirit of higher-level directives. The key to

accomplishing this was a proper attitude on the part of the cadres. The cadres had to prove to

the masses that they were willing to listen to them. They should do this by encouraging mass

discussion of the issues. If an ordinary poor and lower-middle peasant said something that a

cadre did not like, the cadre should accept the remark with good grace. If ordinary poor and

lower-middle peasants disagreed with a cadre, the cadre should win the peasant over with

persuasion not threaten him with coercion. |

|

Yes, there were in fact widespread shortcomings in the use of the mass line, and in the actual practice of democracy, even in revolutionary China during the Mao period. I do not deny it. It is important to note, however, that most of these shortcomings were on the local level. When you look at the big picture, on how the overall Chinese Revolution was led by Mao and the Communist Party of China when he was at its head, the leadership method of the mass line and mass democracy was extremely successfully used to transform the whole country. China really was changed from a backward society suffering from oppressive feudalism and comprador capitalism into a new, liberated, socialist society. That is what counts the most! And that is, overall, what democratically reflected the genuine aspirations of the masses.

If Maoist revolutionaries truly learn the valuable lessons of the Chinese Revolution, including what it means to use the mass line method of leadership and to promote mass democracy with a solid and reliable proletarian leadership core, we should be able to do an even better job of it in the future!

Some Further Discussion on Proletarian Democracy

A number of bourgeois-democratic writers have said things along these lines:

| |

“The real essence of democratic politics is the tolerated presence of an opposition, the existence of parties advocating different principles or methods of government.”[48] |

|

However, I have been arguing that from the proletarian revolutionary perspective the true essence of democracy is allowing people to have real control over their own lives, which can only be accomplished in a combination of individual choices (where only the individual is concerned) and collective democratic decisions (where the many are concerned). So what should our attitude be toward this liberal platitude?

We should partly agree with the first part of the statement, that with regard to collective matters real democracy requires the “tolerated presence of an opposition” and of the right of criticism. However, it must never be forgotten that in class society no ruling class ever truly believes in this principle with regard to allowing the full and widespread expression of views of alien and opposed social classes! In bourgeois-democratic society laws are usually not necessary to suppress any developing revolutionary views of the proletariat; instead, for the most part, the economic system itself takes care of this. Nearly all the mass media is owned and operated by the capitalists, and they don’t hire Marxists! And in socialist society the proletarian state will likewise supervise the media and prevent the overthrown capitalists (or any newly developing bourgeoisie) from dominating and controlling the media and educational systems. We won’t be hiring pro-capitalists in the media or the educational system! It will probably be wise to allow a few very low circulation bourgeois journals to still exist, primarily so that we can keep on eye open to what they are thinking, and so we can continue to point to examples of pro-capitalist, pro-exploitative thinking that still remain in socialist society. But just as the ruling class in bourgeois-democratic society in effect mostly only allows the expression of criticism and opposition within its own class milieu, so too will the revolutionary proletariat mostly only allow the expression of various critical or opposing views from within the proletariat and masses.

We will have to be rather loose and generous in this regard, however! It is all-too-easy to claim that any expression of criticism or opposition to the present status and policies in socialist society is “really” pro-capitalist ideology! And, in fact, sometimes it really will be so, in essence! Some bourgeois ideology will certainly remain among the masses in socialist society, and even within the revolutionary party (though hopefully to a lesser degree). We have to allow wrong, and even clearly bourgeois ideas, to be expressed by the masses at least, as part of the political struggle to combat and correct those erroneous ideas among the people.

The second part of the liberal platitude, however, is a more complicated question. We deny that the existence of multiple political parties (and elections between them) are in general necessary (or desirable) in order for the political struggle of ideas and goals to proceed. If the proletariat is led by multiple opposing parties, how can it ever act in a unified way as a class?! However, we do have to understand that minority factions will inevitably develop among the masses and within the revolutionary party, and that democratic rights of association must permit this to occur, as long as those in the factions are open and above-board and follow the rules of democratic centralism.[49] (More on this in the next chapter.)

Here is the way that Mao summed this all up:

| |

Within the ranks of the people, it is criminal to suppress freedom, to suppress the people’s criticism of the shortcomings and mistakes of the Party and the government or to suppress free discussion in academic circles. This is our system. However, all this is legitimate in capitalist countries. Outside the ranks of the people, it is criminal to allow counter-revolutionaries to be unruly in word or deed and it is legitimate to exercise dictatorship over them. This is our system. The opposite is true of capitalist countries, where the bourgeoisie exercises a dictatorship under which revolutionary people are not allowed to be “unruly in word or deed” but must “behave themselves”.[50] |

|

The Limits of Democracy

As much as I wish to promote democracy in society and in the revolutionary movement, even democracy has its limits and is not always and everywhere appropriate. In some spheres and some respects it is just not appropriate at all. As we just saw above, every ruling class in class society, whether it be the capitalist class today or the new revolutionary proletarian class in socialist society, has to restrict democracy for the enemy class (or classes) in order to be more certain of hanging onto political power in the era of class struggle. So the interests of the proletariat require that full democracy be allowed only for the proletariat itself and its allied classes and strata (i.e., for “the people” in the Maoist sense). It will have to be possible to loosen up on this requirement in the final stages of socialist society, as it nears the full transition to communist society.

There may well be some other contradictions between the full and complete democracy even among the proletariat and the masses in socialist society (especially in its early stages) and the inescapable demands of the revolutionary process. We should recognize this possibility and some of the things it might require, including possibly some restrictions on mass democracy at times. During times of revolutionary warfare, for example, even the democratic rights of the masses may need to be restricted in part.

In a moment I will provide a quote on this general theme from Harry Magdoff, who was one of the editors of Monthly Review magazine. But I want everyone to first brace yourselves, because this self-called “socialist magazine” MR has been rather notorious for not even really knowing what genuine socialism is! They thought that the Soviet Union from the Khrushchev era on was a real (if somewhat deformed) socialist country, when it fact it was simply a form of state capitalism. They were among those who referred to the social-imperialist U.S.S.R. in that era as “actually existing socialism”! And in his old age and up to his death, Magdoff personally argued that China remained a “socialist country” even after Mao’s death and after the capitalist-roaders had totally transformed China into a new capitalist-imperialist country! So keep in mind here that Magdoff is no reliable authority on what socialism actually is or needs to be. Still, there are some points here that we do need to keep in mind even about genuine socialist society. Here is the quote:

| |

Actually, the challenges of a transformation of consciousness, and socialist culture in

general, get pitifully little attention in [what he considers to be!] socialist circles. Instead

the focus is on democracy, usually democracy as an abstract ideal, without regard to social

relations, abolition of classes, or the road to equality. There are tough questions about what

socialist democracy might mean. Take, for example, what many of us believe should be an outstanding

feature of replacing capitalism: giving top priority to empowering and meeting the basic needs of

the most impoverished and oppressed sectors of the population. That would require major changes in

the allocation of resources, the kind of changes which a market system, even one where the

factories are managed by the workers, cannot hope to achieve. |

|

One thing that we Maoists want to insist upon is that a real democratic socialism is not at all the same thing as what is currently called “democratic socialism” or “social democracy”! Those things are not actually socialism at all. (In part because the revolutionary proletariat is not really in power; and in part because they are not even by aspiration a transition stage toward communist society.) However, Magdoff’s remarks here can also be interpreted as pointing out that real democracy can sometimes be in contradiction with the needs of the revolution. And when it is, the needs of the revolution must take precedence! (According to the fundamental principle of proletarian ethics, the genuine needs of the socialist/communist revolution in society are what determine what is right or wrong. This is simply because it is this great social revolution that most centrally answers to what is in the deepest interests of the proletariat and the masses.)

That’s the political situation. But in the sciences the situation is more extreme. While we certainly do promote the democratic freedoms of discussion and for people to hold differences of opinion about what the correct facts and theories in science are, we absolutely deny that the truth of the matter is to be determined by any democratic procedure (such as voting). Darwin put it this way:

| |

When it was first said that the sun stood still and the world turned round, the common sense of mankind declared the doctrine false; but the old saying of Vox populi, vox Dei [the voice of the people is the voice of God], as every philosopher knows, cannot be trusted in science.[52] |

|

Each science will have to struggle out for itself what theories and facts are correct, and will inevitably have to extend and correct itself as it further develops. It is through experience, further experiments, and other forms of investigations that are confirmed by other scientists that scientific truth is determined. Of course the dominant views among the practitioners of any science are likely to be correct most of the time. So, in this sense, it is normally reasonable for those attempting to apply the existing results in any science to follow the “generally held views” of scientists in that field. This is sort of a practical concession to democracy in the use of current scientific knowledge for the benefit of society. Nevertheless, it is virtually always true that new advances in science will at first be discovered and held by either a single scientist, or else by a very small number of them.

Stephen Jay Gould expressed the main point here this way: democracy “just doesn’t apply to the evaluation of information.”[53]